Using open content in the new Sound & Vision exhibition

This year, the Dutch public radio station 3FM celebrates its 50th anniversary. The first broadcast of the station - then still called Hilversum 3 - took place on 11 October 1965. From the start, the station focussed on pop and rock music, later supplemented with electronic, house and dance music. The Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision marks this anniversary with a dedicated temporary exhibition, 3FM presents: Your Serious Radio. The exhibition focusses on the importance of music and radio in your teen years. It does so through showcasing DJs from all eras of 3FM, featuring hits and radio jingles from the 1960s to now, and by letting the visitors experience what it’s like to produce a radio show.

Videomapping your teen room

When visitors enter the exhibition, they can provide information that builds up their personal profile: Their year of birth, gender and their favourite radio show, song, musical genre from their teens. All this data is stored in the RFID-chipped ring that Sound & Vision uses throughout its entire museum. This profile is used extensively for one of the key interactives of Your Serious Radio: a videomapping installation of a teen room.

The installation is built up from a sparse white space split in a sitting and sleeping area, with 25 different elements like a white bed, desk, and couch. These elements are projected upon when a visitor activates his or her personal profile with the ring. Besides interior decoration, posters from artists related to their favourite musical genre are also projected, as are t-shirt designs fitting with their “sweet sixteen” period.

Fig. 1: The default, videomapping space. Sitting area on the left, sleeping area on the right.

At the very beginning of the process, it was decided to divide the period of the exhibition (1965-2015) into ten time periods: 1965-1969, 1970-1974 and so forth. By doing so, the profiling software could categorise visitors into these segments, by calculating when they would have been sixteen. A visitor born before or between 1949 and 1953 would have been sixteen in 1965-1969 and would therefore fall into that time period. Together with their gender and musical genre preference, this provides enough granularity to curate a nice, recognisable teen room.

At first, we wanted to have visitors pick from eight musical genres per time period and have these influence the decor of the room. Quick calculations however made clear that this would require researching tens of thousands of images, and this was quickly let go. In the end, visitors can choose four music genres per time period, which only influences a relatively small part of the entire videomapping spectrum and resulted in having to find hundreds of images, not tens of thousands.

Fig 2: Teen room videomappings. Top to bottom: teen boy folk music fan, 1965-1969; teen girl pop music fan, 1990-1994; teen boy house music fan, 1990-1994.

Fig 2: Teen room videomappings. Top to bottom: teen boy folk music fan, 1965-1969; teen girl pop music fan, 1990-1994; teen boy house music fan, 1990-1994.

Seamless research

In some cases, we needed images of artists and bands that fit the genre picked by the visitor, to project on the wall of the room as posters. But for the most part, we needed so-called “seamless” or “tileable” patterns for the interior elements, like the couch, the floor and the wall. All these elements are created in a 3D virtual world, and depending on the visitor’s information, the seamless patterns are projected and repeated on each of these elements. For example, in order to project a certain pattern on the wall, 3D software needs to be programmed in order for this pattern to represent e.g. a 50cmx50cm part of the wall in the physical space. This pattern is then repeated across the entire wall. Since the pattern is seamless, the wall appears to consist of one big piece of wallpaper. Technically, this is easy to accomplish, but to actually make sure you’ve found a perfectly seamless pattern, you sometimes need to check this in photo editing software. If there’s a problem, you will definitely see this during projection.

Fig. 3: Early test with a wallpaper that looks great, but that was not seamless enough; lines showing at the edges of each tile.

Fig. 3: Early test with a wallpaper that looks great, but that was not seamless enough; lines showing at the edges of each tile.

Open content: searching and considerations

There was not a lot of budget to buy content from stock image websites, and moreover, Sound & Vision is an open content enthusiast (both as user and as supplier). The latter means that Sound & Vision has an active “open, unless” policy, which means that when we have the rights of content in our collection, we make it available under open Creative Commons licenses or under the Public Domain Mark (if rights have already expired). This allows our collection to find its way to open initiatives like Wikipedia through platforms like Open Images, SoundCloud, Open Culture Data and our own Wiki. Thus, we have a lot of experience with opening up content. However, searching for and using open content provided by others for our own exhibitions was not a common practice by any means.

Important questions we had were: What are optimal search strategies, can we find enough open content, how do we provide correct attribution, do all Creative Commons licenses allow the type of usage for our videomapping, how can we know for sure that what we find is indeed published by or as agreed upon by the rights holder? These questions will be answered in more detail below.

Is there enough content out there?

Not everyone at Sound & Vision has a lot of experience with open content. There was some doubt whether we would be able to find enough material, in order to create the right look and feel for each time period and all music genres. Even yours truly -- long-time open content creator, user and enthusiast -- questioned whether we’d find a significantly high amount of the required content. But some quick searches (e.g. “retro pattern”, “1980s texture”) on Wikimedia Commons and Flickr yielded enough results to feel confident to pursue the open content route.

Fig. 4: Left to right: Swordfish wallpaper by deanoakley, CC BY; ’80s Geometric Pattern by RetroVectors, freely usable; Fabric textured design coarse by ZIPNON, CC0.

Fig. 4: Left to right: Swordfish wallpaper by deanoakley, CC BY; ’80s Geometric Pattern by RetroVectors, freely usable; Fabric textured design coarse by ZIPNON, CC0.

Which licenses permit us to use the content as we want?

The most important question for us was: Are all six Creative Commons licenses fit for our purpose? The no-derivative requirement turned out not to be a problem for us: We are projecting all images as-is. And even if they become part of a larger whole, the original image would not be adapted. The non-commercial clause warranted a bit more study, since the concept and interpretations can vary and are a bit vague. To this end, we looked into two important resources offered by Creative Commons itself on this topic: An explanatory page on the interpretation of the NonCommercial element, and a study done on the interpretation of both creators and users on the terms “commercial” and “noncommercial”. Sound & Vision is a non-profit organisation, but does get revenue through tickets sales of the exhibition in which we use the content. Thus, we are not a “non-commercial” entity per se. However, a very important distinction we found in the resources above, and in the language of NC-licenses is that our use is not “primarily intended for or directed towards commercial advantage or private monetary compensation.” This made us confident that our intended use was within the scope of any NC-license. Furthermore, we decided to notify all creators of whom we use content about our use within the exhibition. If they are to object, we can easily replace it.

Credit where credit’s due: Providing attribution

All six Creative Commons licenses require attribution. But since we’d use hundreds of images for the videomapping, we could not attribute each and every image in the physical exhibition. We decided to point to a link in the physical exhibition colophon to an extensive online colophon with a link to a Google Spreadsheet with an overview of all content used. By doing so, for the Attribution and Attribution-ShareAlike licenses (and all Public Domain and CC0 content), we felt very comfortable that we were honouring them as best we could.

How to search

Before we started researching, we drafted search guidelines to help the art directors find and identify open content. Main sources and approaches in these guidelines were:

- Wikimedia Commons. All content on Wikimedia Commons has an open license limited only to attribution and share-alike requirements or is in the Public Domain. This proved to be an important source, in particular for pictures or bands and musicians.

- Flickr. Many photographers, designers and other image creators open up their content under an open license on Flickr. The platform has an easy search filter for Creative Commons licenses.

- National Archives of the Netherlands. The Dutch National Archives has an amazing and vast collection of openly licensed pictures (CC BY-SA, over 400,000 images)

- Google Image Search. The Search Tools in Google Image Search has a ‘Labeled for reuse’ filter. Since Google also searches in Wikimedia Commons and Flickr, this was often the first resource consulted. But sometimes going directly going to websites allows you to break out of the Google ‘filter bubble’ and find more results.

- Doornroosje poster archive. The Regional Archives of Nijmegen have released the poster collection of music venue Doornroosje on Flickr. Since we needed music-related posters in our exhibition, this was a great and fun source to pick from.

Later on in the process, we found the open stock-image site Pixabay (all content CC0!) and Creative Commons Search to be indispensable sources as well. The latter is valuable, since it is an easy search entry point to Europeana, with its millions of open content resources that as of yet do not pop up in Google Images Search.

Is content REALLY open?

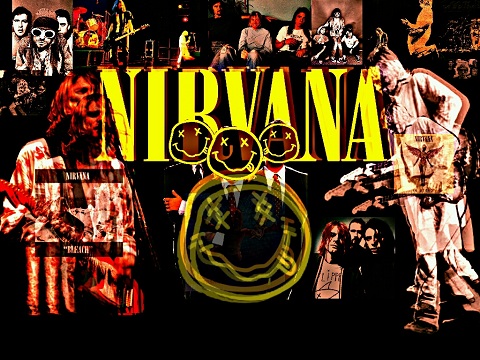

Sometimes, we found content that was provided under an open license by someone, but that we either doubted was created by themselves or that was obviously made by somebody else, like in the image below.

Fig. 5: Example of a compilation of works by various creators, uploaded by a user on Deviant Art under a CC BY-ND license. The user does not have the copyright of the remixed images, and can thus not use any of the Creative Commons licenses.

Fig. 5: Example of a compilation of works by various creators, uploaded by a user on Deviant Art under a CC BY-ND license. The user does not have the copyright of the remixed images, and can thus not use any of the Creative Commons licenses.

In those cases, we decided not to use the files. In the case of Wikimedia Commons, ‘suspicious’ content was flagged for deletion. This means that the Wikimedia community can decide whether this flagging is indeed correct and proceed to delete the file in question.

Fig. 6: Example of a file flagged by Sound & Vision staff, since deleted by the Wikimedia community.

Fig. 6: Example of a file flagged by Sound & Vision staff, since deleted by the Wikimedia community.

Sometimes, people did use a Creative Commons license for content they made themselves, but indicated in the description that they would prefer it if people did not re-use their image without asking them. In those cases, we also decided not to use the content.

Open and closed division

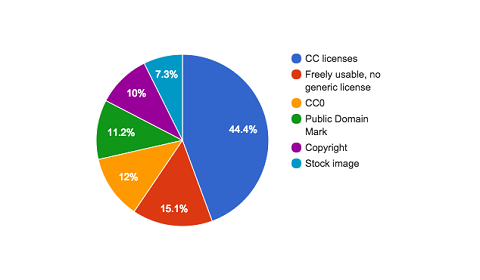

In the end, we gathered 254 individual textures, patterns and pictures needed to cover all time periods and all music genres. 44% of these files are explicitly openly licensed with one of the six Creative Commons licenses and almost a quarter is in the Public Domain (11% PD-mark, 12% CC0). 15% of the content is freely usable, but does not have a generic, world-wide acknowledged open license, like Creative Commons, but for instance a comment by the user that anyone is free to use their content as they please or a website-specific license like CG Textures. So, in total, well over 80% of the individual content used is freely usable. The rest is stock material (7%) or copyrighted material (10%), either from Sound & Vision’s own collection or for which we either got direct usage permission of the rights holders or through collective rights organisation Pictoright.

Fig. 7: overview of division of rights status of content used in video mapping

Fig. 7: overview of division of rights status of content used in video mapping

Open content gaps

We had the most difficulties finding openly licensed pictures from bands and musicians from the 1990s. We ended up using pictures from our own collections and even took screenshots from programmes in our archives from this time period. In particular rock, grunge, house, and ‘gabber’ hardcore music were hard to find. It’s safe to say that the nineties generation still needs to get their act together and scan their analogue pictures from concerts and festivals from that time. A good example is this Red Hot Chili Peppers wiki-article that only has 1980s and more recent images. Our current theory is that the generation that grew up in the 1980s and before has gotten around to spending time on scanning and uploading their pictures due to early retirement and growing nostalgia. The advent of digital photography and explosion of camera phones in particular in the 2000s has contributed to these eras offering more rich open content online. The nineties Millennials should start to catch up!

Contacting creators

The final step in the process will be contacting the people whose open content we used for the projection, not just to thank them, but also to send them pictures of how their content looks in the final result. Curious yourself? You have until June 2016 to visit 3FM presents: Your Serious Radio at Sound & Vision. If you can’t make it, you can find all the pictures of all the rooms here.

Final thoughts

In the end, we are very happy that we managed to find over 80% of quality content that is freely usable. This demonstrates how important open licenses are for stimulating creative reuse. We could have never afforded to buy all 250+ images from stock image websites or license pictures from bands and musicians. Now, we paid a few hundred euros for licensing. Although the ‘open’ approach took quite some research hours, the end result is superb. We are proud to show it and look forward to many people seeing their teen rooms in 3FM presents: Your Serious Radio.

Videomapping credits

- Technical realisation: Kiss the Frog.

- Design: Pièce Montée.

- Research and Art Direction: Bij de Tijd and Sound & Vision.

- Project management: Sound & Vision.