Heritage under threat

Audiovisual collections are vulnerable in uncertain times. How can they be kept safe? And how was this done in the past?

Read later

Climate change

Audiovisual heritage is under threat, also in Europe. For example, due to the effects of climate change, such as the 2024 floods in Valencia. Or closer to home: the flooding in the bunker where the Eye Filmmuseum stores its nitrate films. Here Eye employees are working hard to prevent further damage.

And what about military conflicts, such as the war in Ukraine?

In this clip from the ‘NOS Journaal’ news programme, Russian forces attack a television tower in Kyiv... The archives are not safe either.

Cyberattacks

And then there are cyberattacks. In September 2021, for example, there was a attack on the Swiss film archive. The digital lab was badly affected: machines were out of action for months, and two film restorations were lost. The film department also came to a standstill because databases and scanning stations were down.

1930s

However, the threat to audiovisual heritage is anything but new. Since the 1930s Dutch broadcasters looked for ways to preserve their audio collections. Plans for a national audio archive were being discussed and Dutch broadcasters already took measures to safeguard their recordings. In 1936, for example, the AVRO moved into this new building in Hilversum, complete with dedicated archive rooms.

AVRO also had state-of-the-art recording equipment for recording radio broadcasts.

These recordings were mainly used to create new programmes, not to preserve them permanently.

German Occupation

But then the Second World War breaks out. In May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. Not long after, German propaganda troops arrived at the AVRO complex. They brought enough Dutch-language records with them to cover two weeks of broadcasting. They also took over the central control room of Dutch radio. Political recordings from the archive were taken to Berlin.

“Very vulnerable”

Broadcasting company employees immediately realise how dangerous it can be to possess archive material under German occupation. At VARA, they took a drastic decision: they burned anti-fascist materials from their archives. AVRO also took action, as radio archivist Bep van Heukelom-van den Brink recalls in this oral history interview.

In 1941, amateur filmmaker Theo Uden Masman captured these images of the AVRO building in Hilversum.

From the outside, everything seems normal, but inside there is resistance.

Employees rescue material that the Germans want to confiscate.

For example, they hide glass records containing historical speeches by the Dutch royal family under an elevator.

At night, a sound engineer makes copies that trusted colleagues smuggle out during the day.

After the Liberation in 1945, they hand over the recordings to the authorities.

This shows how important they considered the material to be.

German Bunker

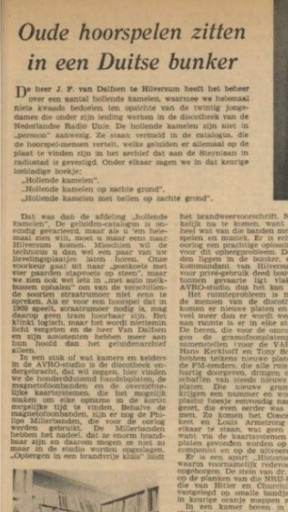

During the occupation, AVRO managed the archive material of all the Dutch broadcasters, and from 1947 onwards also that of the (NRU). During this period, the archive staff realised that not only music was worth preserving, but also spoken word programmes, such as radio plays. They stored the radio plays in a former German bunker in Hilversum, whose cool temperature offered some protection for the flammable sound film strips on which the radio plays were recorded.

In the 1950s, the archives of the broadcasting companies grew enormously, especially after the arrival of the new FM transmitters.

The buildings became overcrowded. Where could they store all those tapes and records?

As a solution, a sound archive was established at the present-day Media Park in Hilversum.

This modern 'Muziekpaviljoen’ (music pavilion) features climate control, listening booths and a music library, among other things.

There are also plans to use computers to improve lending to programme makers.

Political Speeches

In the early 1960s, there was a growing awareness that the archives of the broadcasting companies also had great cultural value. Take, for example, the NRU's lacquer discs containing speeches by political figures. Surely these should be preserved? Coenraad Brandt, professor of Modern History, was committed to this cause. He collected the speeches and stored them in a special sound archive at Utrecht University. In 1970, this archive was transferred to the .

Cultural Heritage

With the ratification of the in 1972, there was a growing awareness of radio and television recordings as cultural heritage. At that time, the NOS only preserved a fraction of its radio broadcasts. Staff at the raised the alarm and ensured that Dutch broadcasters began to supply more material. Within the broadcast organisations, there was growing attention to the management of production archives: they invested in electronic databases, tape preservation copies and new methods of archiving.

Sound & Vision

In 1997, a merger resulted in the creation of the Netherlands Audiovisual Archive. Its goal was clear: to build a national archive that would preserve audiovisual heritage, particularly broadcasting material, and make it available to broadcasters and educational institutions. In 2006, the archive opened its iconic, colourful building at the Hilversum Media Park and changed its name to the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, or Sound & Vision for short.

From that point on, Sound & Vision shifted its focus to digitally securing the archive and making it available to the public.

In this clip from the Dutch children’s programme ‘Het Klokhuis’, you can see the Sound & Vision digital archive in action.

Radio and television programmes are automatically fed into a large server.

A robot takes care of delivery.

This is how Sound & Vision manages our Dutch media heritage, both now and in the future.

At the same time, it stays sharp to outside threats that could endanger the collection.

What do you see as the greatest threat to audiovisual heritage?

The protection and preservation of audiovisual collections remains a significant endeavour. Initiatives such as the UNESCO World Heritage Convention have raised awareness of the need to care for and protect this heritage, as reflected in the mission of institutions such as Sound & Vision. At the same time, history teaches us how vulnerable audiovisual collections are in times of war and political pressure. Today, new risks are emerging, from cyber attacks to climate change. That is precisely why the efforts of heritage professionals and organisations remains indispensable.

Bekijk ook

Op 21 januari organiseert het ANP namens BENEDMO een gratis workshop voor journalisten over het vinden en beoordelen van (open) data. Je krijgt praktische tools, leert bronnen kritisch te evalueren en werkt aan hands-on cases.